For nearly 100 years, the United States has been the world’s leader in a wide variety of scientific fields. No other country has:

- invested as much in fundamental scientific research,

- has made more scientific breakthroughs and scientific advances,

- has attracted more scientific researchers to move there to conduct their research,

- or has conducted more projects and been home to more scientists that have won Nobel Prizes.

From public health to food safety to clean air and water to vaccines to dental health to disease eradication and pandemic prevention, the United States was the world leader. From rocketry to space exploration to planetary science to astrophysics, heliophysics, and Earth monitoring, the United States’s standing in the world was unparalleled. From education to energy, from chemistry to biology, and from environmental science to medical breakthroughs, no other country came close.

And yet, this past year — 2025 — has seen much of that scientific legacy dismantled. Facilities and libraries have been closed. Thousands of our best and brightest scientists have had their government positions eliminated. Projects have been canceled and/or defunded. Even entire governmental departments and organizations have been terminated, including the Department of Education and HEPAP: the high-energy physics advisory panel.

Scientists and non-scientists alike have fought back with great vigor against these cuts, and a newly agreed-upon congressional budget promises to restore key levels of funding to several organizations, including NASA’s science mission directorate and the National Science Foundation. It’s vital that we keep fighting for a solid scientific foundation (and future) within the United States, but that alone won’t lead us to the future we need. Here are the four key paths forward for US science and scientists: not only here in 2026, but beyond as well.

1.) Keep fighting for the continued funding of our current-and-future projects and scientists.

This is not a drill: in 2025, an enormous number of projects, agencies, and scientists had their funding and positions cut, withdrawn, or eliminated entirely. At the start of 2025, there were over 17,000 people employed by NASA; as of today, in mid-January of 2026, that number is down below 13,000: a reduction of more than 4000 of the most skilled and qualified members of the US workforce. NASA’s Science Mission Directorate saw the largest funding cut in its history proposed in 2025, threatening to close out, cancel, or otherwise eliminate many of the most ambitious opportunities for 21st century science in the entire world.

The threat to science, in many ways, has been existential and across-the-board, and astronomical/space science at NASA and the NSF have been no exception. The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope — NASA Astrophysics’s next flagship mission after JWST — was completed ahead of schedule and under budget, and its reward was being denied sufficient funding to launch it. Mission control at NASA Goddard’s Space Telescope Operations Control Center (STOCC) was slashed, threatening the necessary resources to operate our already-existing space telescopes, not to mention new ones. The Thirty Meter Telescope was cancelled by the National Science Foundation; NASA’s Mars Sample Return mission was eliminated; thousands of NASA employees were compelled to face early termination; the world’s flagship solar observatory (DKIST) was forced to reduce operations; many of the most prestigious fellowships and opportunities for early career scientists were taken away by the hundreds.

Importantly, a lot of people fought back. Organizations, including:

- the American Astronomical Society,

- the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine,

- the American Physical Society,

- the American Association for the Advancement of Science,

as well as thousands of professional scientists at all stages in their careers, sounded the alarm and refused to remain silent. Warnings were issued, letters were written, even whistleblowers at various federal agencies, despite orders not to talk about what was happening, spoke up. Campaigns were waged on Capitol Hill, congresspersons and senators were contacted, and much, much more. In the first week of 2026, at last, a new congressional budget agreement was reached, setting the stage to restore much (but not all) of the needed funding to NASA and NSF, among others.

This path — which one can think of as “plan A” — is a path that has worked many times throughout history, as new NASA Astrophysics Division Director head Shawn Domagal-Goldman reminded listeners at the recently-completed 247th meeting of the American Astronomical Society. However, this path isn’t working for everyone, including:

- the thousands of US scientists who’ve lost their jobs,

- US projects that have had their US contributions cancelled, such as Mars Sample Return mission and the Thirty Meter Telescope (although the Thirty Meter Telescope has been ordered to proceed to final design phase in the new congressional budget, albeit without funding),

- or the facilities and sets of infrastructure that have already been closed or repurposed.

The “plan A” path might work for some missions, and possibly even the future Habitable Worlds Observatory, but there are three other paths that everyone, from mission directors to project scientists to professors to researchers to students, should strongly consider investing in as well.

Credit: NASA

2.) Plan a contingency in the event that the US Government suddenly rips out the rug from under you.

As 2025 definitively proved, the US government might, at any moment:

- cut off already-appropriated funding for your project,

- reorganize and eliminate the overarching, governing structure for your project or career,

- revoke the visas of any international scholars participating in your project,

or much, much worse. The track record from 2025 shows that everyone from agency heads down to early career scientists faced termination, irrespective of the merits of either their project or their own actual work. While this came as an unprecedented surprise to many in 2025, it will not be a surprise moving forward; projects, agencies, organizations, and individuals know to expect this now.

And that’s why everyone who has either a job working in science for the US government or has a project that relies on US government funding should be working on a “plan B” in the event that their project, career, or contract suddenly has the rug pulled out from under it. Contingency plans are varied, but will include:

- looking for private investors or other alternate funding streams to replace any funding that the government might yank,

- relying on international partners to fill in the gaps that will be left by the US government abandoning your project,

- seeking the cooperation of academic societies from around the world to provide facilities and infrastructure for any displaced scientists,

and much more.

Credit: NASA/International Space Station

The fact is that the entire world has taken notice of the US government’s unreliability to be a stable, long-term funding partner in any long-term ventures. (And yes, fundamental scientific research is always a long-term venture.) Despite the recent victory for science funding to open the new year, many are anticipating renewed attacks on the scientific foundation of the United States across the board. The European Space Agency, for example, has expressed reservations about its EnVision probe, and in particular about the NASA-made instrument VenSAR that’s supposed to fly aboard it.

The space-based gravitational wave flagship mission, LISA, is considering abandoning their NASA partnership, with Max Planck Institute professor Guido Mueller stating, “My biggest concern is if they say that they will do it and then pull out five years later. For LISA, that would be a huge disaster because at that point, everything would be going into flight hardware, everybody here has industrial contracts that we would have to continue to pay while trying to catch up on the hardware development that NASA should have provided.” All told, 19 joint space science missions, plus the ExoMars rover, would’ve faced funding shortfalls or even outright cancellation under the Trump administration’s earlier proposed budget.

As David Spergel of the Flatiron Institute and the Simons Foundation put it, “There are two possible futures for American science. One is that this proposed budget is a bump in the road and funding will stay at close to the same level. A second version is where this represents a real sea change in the relationship between government and science funding. I don’t think we know what world we’re in yet.” To not make contingency plans in today’s world is an extraordinary gamble: one that might lead to a trap door opening beneath your project’s — and your career’s — feet.

Credit: University of Florida/NASA

3.) Attempt to salvage-and-save the projects, careers, and opportunities that have already been terminated here in the US.

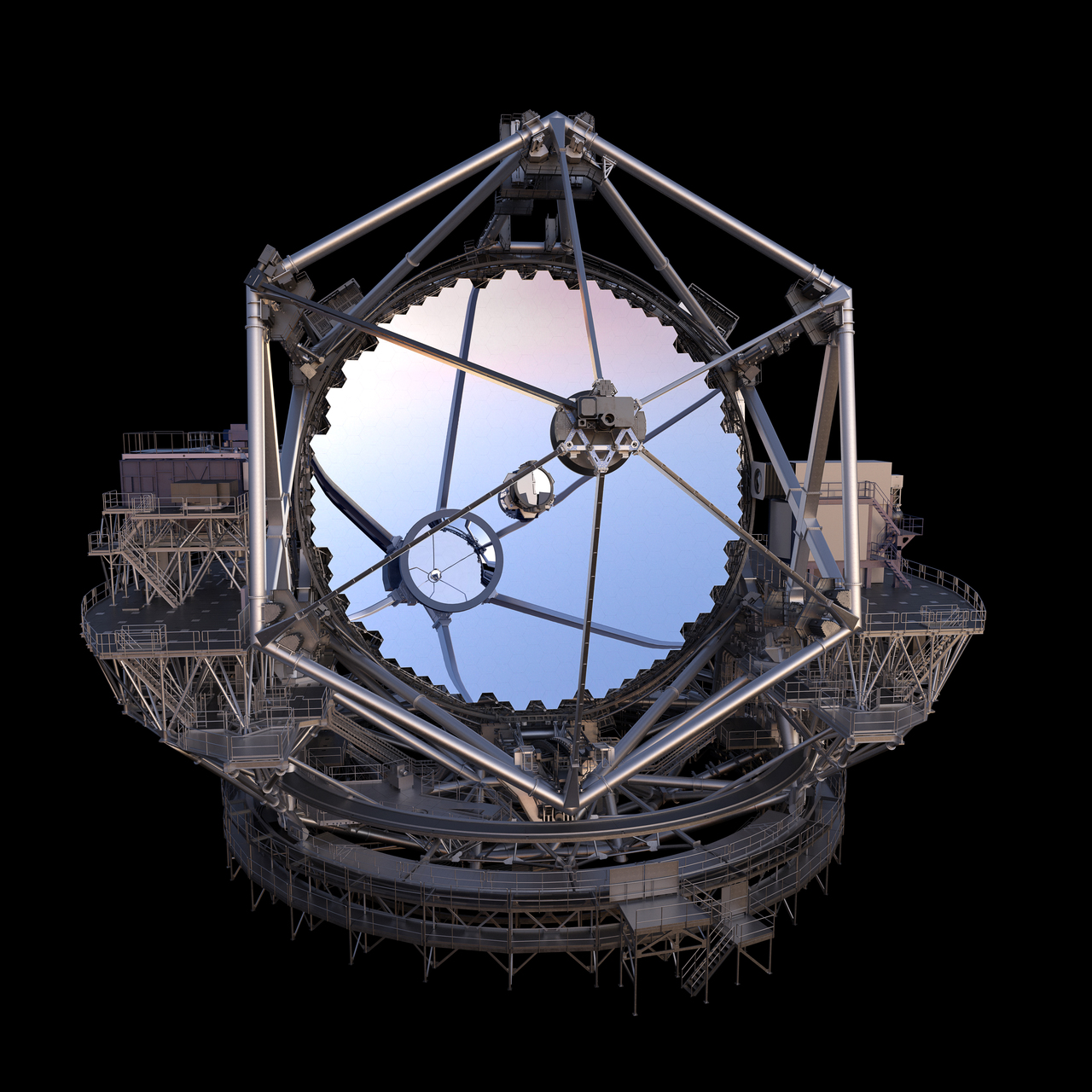

Will there be a Mars Sample Return mission happening in the 21st century? Perhaps, but it will likely be a nation like China or Japan that does it, not the United States, as it’s been eliminated from NASA’s plans. Will there be a Thirty Meter Telescope? Perhaps, but it likely won’t be part of the National Science Foundation’s arsenal of telescopes, and at this point it’s looking increasingly unlikely that it will be built on US soil at all. Over 8000 student visas have been revoked, along with around 2500 specialized worker visas: an absolutely essential part of an internationally competitive workforce.

Overall, a record-high number of US-based scientists are leaving or considering leaving the United States entirely, accelerating the already-in-progress brain drain that many have been warning about in scientific circles: a brain drain comparable to the one that occurred in Germany during the 1930s. Fortunately, science is not restricted to one country, but instead is a global endeavor.

- Europe is investing nearly a billion dollars in attracting top (formerly-)US talent, offering special additional funding for researchers to move their labs overseas.

- Japan has built a fund of ¥100 billion to attract researchers from abroad, including offering special positions for displaced scientists.

- Canada and Australia are also offering funding for early career researchers, attempting to close the gap left by the US’s abandonment of their careers.

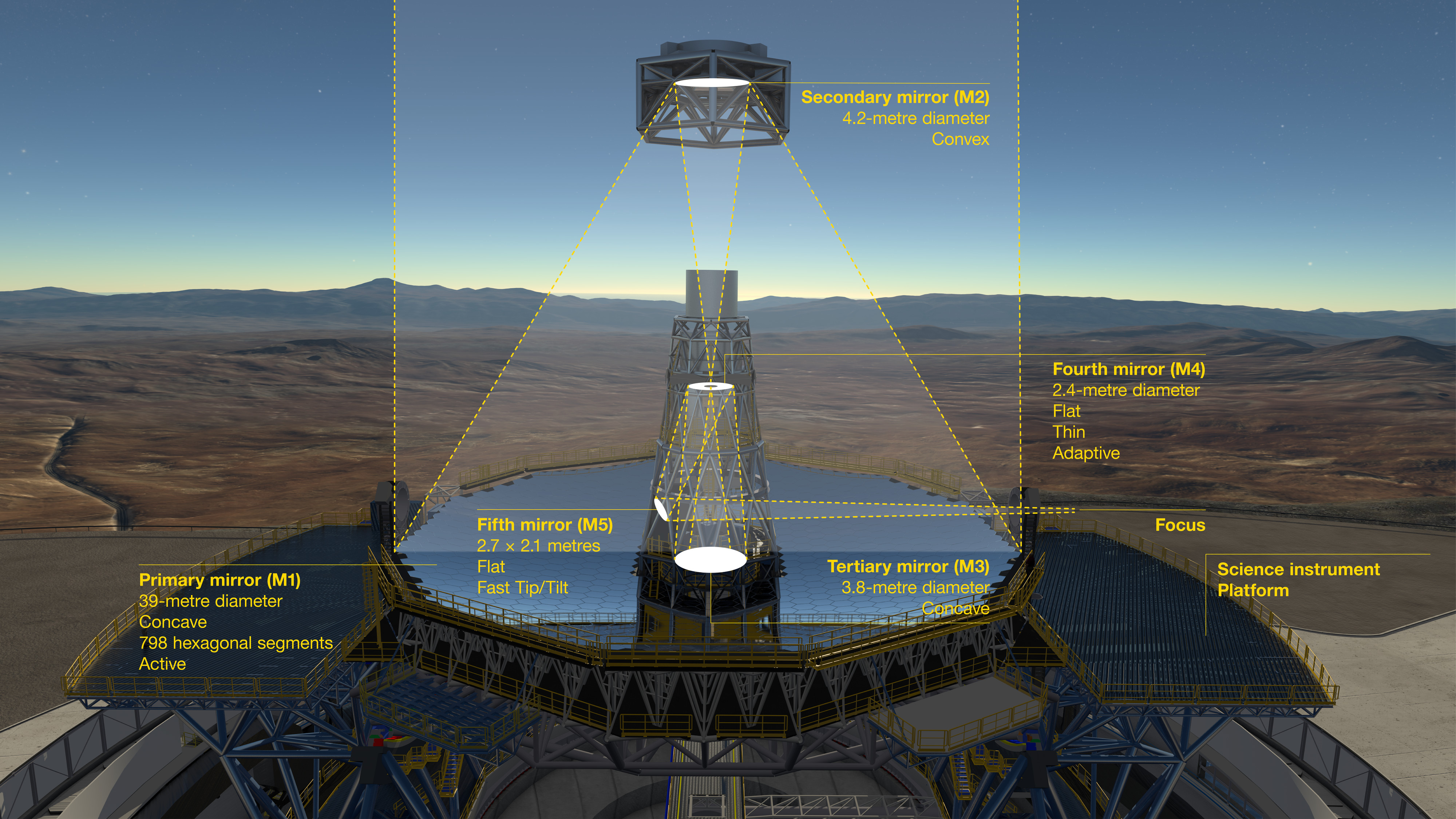

Credit: TMT International Observatory

Whether funded by private donors, philanthropists, research consortiums, or other nation-states — all of which are options for funding that should seriously be considered — just because the United States has pulled the plug on many projects of high scientific merit and high value to humanity doesn’t mean that they need to be lost entirely. Research on a wide variety of topics, including:

- on sustainable energy solutions,

- on high-energy physics,

- on pandemic prevention and mitigation,

- on climate change, natural disasters, and extreme weather events,

- on environmental sustainability,

- and in space science and exploration,

is not confined to any one nation, and perhaps never should have been.

Science benefits all of humanity, and rather than simply focusing on what can be saved within the United States, there should be extraordinary efforts made to save all of the research and all of the researchers whose careers and funding have been (and that will be) canceled and/or defunded in the United States for the good of the world. While the US diverts the resources that should be protected for fundamental research toward dubious but expensive endeavors like large AI datacenters and nuclear reactors on the Moon, basic science will largely have to continue elsewhere in the world.

The scientific foundation of modern society is a bit like an intricately constructed sand castle: it takes a great many people a great deal of effort to build it, but it can be destroyed in mere seconds not even by great deliberate force, but merely through the carelessness of a briefly unattended toddler. That is why it’s critical to save the science that’s already suffered under the chopping block of American politics: not just for the country or for the individual researchers, but for the good of the world.

4.) Work on a long-term plan to rebuild American science after the destruction has ceased, and to rebuild it in a way that will be resilient against the whims of any one political administration or party.

Someday, no matter how impossible it may seem at present, the current storm will be over. There will be no more worries of the unilateral destruction of science or scientific projects — the foundation of our modern, civilized world — coming seemingly out of the blue from the governments designed to support and steward them. Whatever remains of American science, whether it’s something comparable to what still exists today or something much less, will be ready to be rebuilt.

Ideally, we’ll want to build a new set of scientific infrastructure that won’t be subject to the whims of our political winds or the personalities that advantageously manipulate them. We’d want to build a world where foundational science remains our bedrock: where funding for our scientists and our scientific endeavors is guaranteed to persist. There are many different ways to do that, including:

- setting aside the entirety of a budget for a project right from the outset, where it cannot be touched or diminished by outside forces,

- for guaranteeing funding for projects and their personnel outside of the scope of “discretionary budgeting” that can vary or cease from year-to-year,

- or by explicitly writing it into a new constitutional amendment (or a new constitution entirely) that cannot be violated by any governing body, including the country’s leader.

Credit: ESO

It’s easy, particularly here at the start of 2026 when there are reasons for optimism for at least some aspects of science funding in the United States, for people to gravitate only to the first option: to what many have called “plan A” in the fight for a continued investment in fundamental science in the United States. It’s easy to look at some of the private and philanthropic efforts that have gone into funding science, which are of extreme value and importance, and wonder if foundations such as the Kavli Foundation, the Sloan Foundation, the Moore Foundation, the Simons Foundation, and the newly announced Schmidt Observatories, will make up for whatever shortfalls arise from the US government.

Both of these routes are of course tremendously important. It’s important to fight for science in the United States, and for all of us to work together to save as much of it as is humanly possible. Science and sustained investment in it, as has been well-documented, is essential to a modern, functioning society. According to UNESCO, of everything that humanity has ever done or created, “science is the greatest collective endeavor.” And that’s precisely why we must not merely rely on any single institution for its survival. Not on the US government, not on private funders or the philanthropy of the super-rich, and not even on the full suite of plans that we can concoct.

We will need to build a new system: one that’s resilient against the exact types of cuts that we’ve seen afflict science funding over the past year, and is resilient against whatever attempted cuts will take place over the coming years.

Credit: NASA/Chris Gunn

To those of you who are working on the first part of the plan, of saving as much of the science, and as many of the science careers, as can possibly be saved here in the United States: please, keep pursuing those opportunities, anywhere and everywhere you can find them. To those of you who are making contingency plans for how to save your scientific projects and personnel if-and-when your promised funding falls through: absolutely, keep doing this; there will very likely come a day, perhaps even soon, when the groundwork that you’re laying today can save the projects and careers that would otherwise simply be terminated.

And to those of you working on the latter two plans:

- working on saving science and scientists for humanity,

- including by taking projects and people overseas,

- or working on a long-term plan to rebuild American science in the aftermath of whatever’s going to happen in the short-to-long-term future,

rest assured that you are working on creating and preserving opportunities in science that the entire world will someday benefit from, perhaps more greatly than by any other set of endeavors on this list. There are a lot of tough choices that many of us are having to make here in 2026, including among scientists across the nation and world. Whichever of these plans is the right one for you to pursue, rest assured that there will be others working alongside you, while still others will choose to work on the other three. It will take all of us, working on all of these plans, to build the stable, resilient scientific future that the world truly needs: now more than ever.

This article The four paths forward for US scientists in 2026 is featured on Big Think.