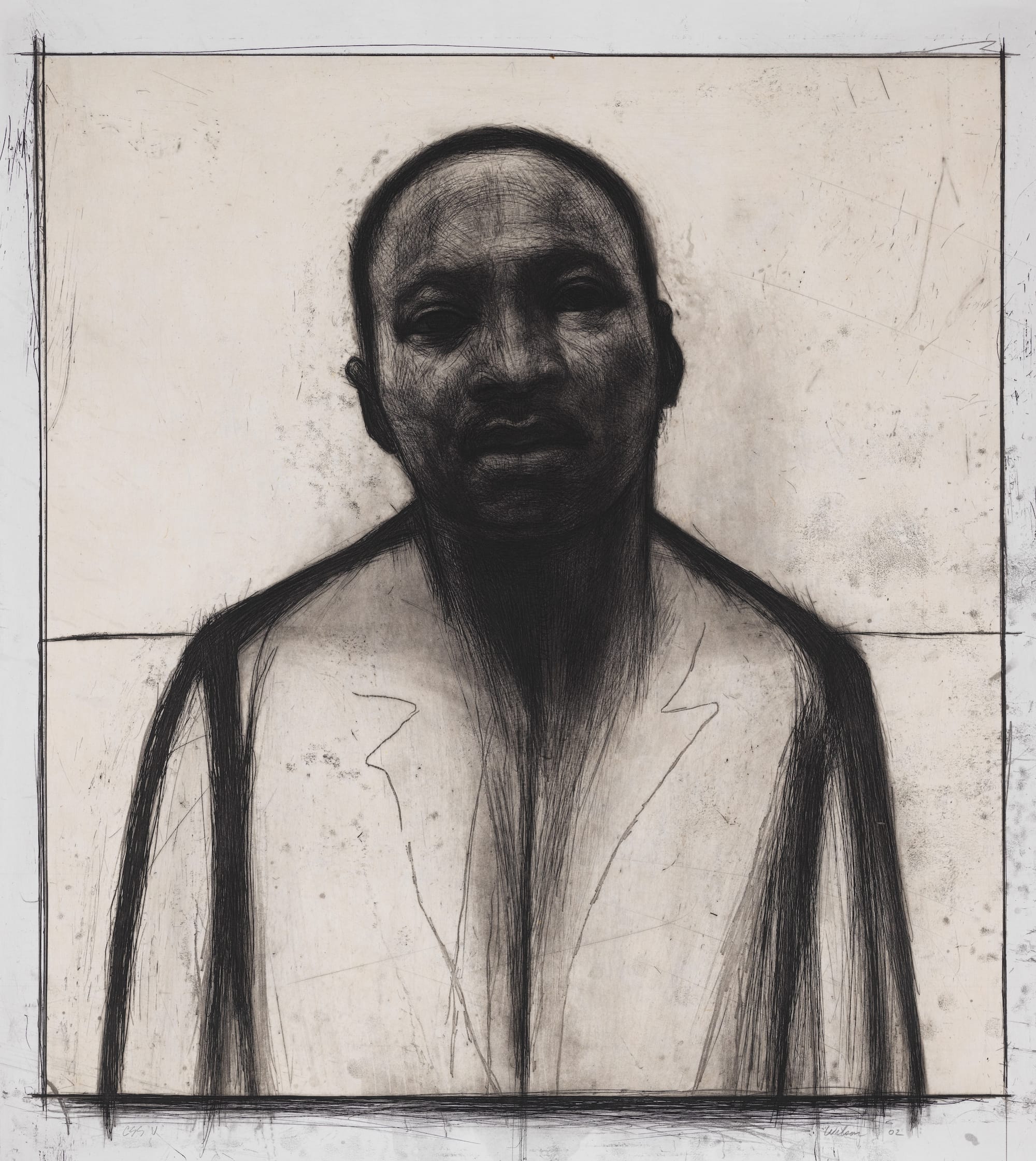

I was on my way to one of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s blockbuster exhibitions when something unexpected stopped me: John Wilson’s “Self-Portrait" (2002). This haunting, abraded pastel and paint work is part of the revelatory exhibition Witnessing Humanity: The Art of John Wilson.

A longtime resident of Boston, a city that never developed an artistic identity as strong as New York’s or some other major US cities, Wilson was a painter, public sculptor, printmaker, teacher, children’s book illustrator, and activist. He was known and respected among fellow Black artists, yet practically invisible in the mainstream, White art world to the extent that his work is seldom included in surveys of modern and contemporary Black artists working in the United States. This much-needed exhibition — originating at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which holds the largest single collection of his art, at 90 works — should bring him the visibility he has long deserved.

Wilson’s parents, who immigrated to the US from British Guiana (now Guyana), encouraged him to study art at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. When he realized that Black people were not represented in the museum’s collection, he devoted himself to “witnessing [their] humanity.” This realization anticipates that of internationally recognized Black contemporary artists such as Kerry James Marshall, who told Griselda Murray Brown of the Financial Times, in 2018: "It’s less about changing the narrative than it is about participating, being a part of it.”

After graduating from Tufts University (which is connected to the School of the Museum of Fine Arts), he received the James William Paige Traveling Fellowship in 1947. It enabled him to go to Paris, where he studied with the French artist Fernand Léger. Wilson was attracted to Léger because of his socialist and humanist beliefs, and his commitment to celebrating the dignity of workers. These convictions would grow stronger for Wilson over the years, setting him apart from the American avant-garde’s growing commitment to art for art’s sake, a stance from which many Black artists felt understandably estranged, particularly at a time when the Civil Rights movement was beginning to foment.

In the summer of 1949, after returning from Europe, Wilson taught at Camp Wo-Chi-Ca (an acronym for Worker’s Children’s Camp) in New Jersey, where he met Elizabeth Catlett and Paul Robeson. The next year, he visited Mexico on a John Hay Whitney Foundation grant, where he stayed until 1956, studying mural painting in Mexico City, and connecting with David Alfaro Siqueiros. His classmates included Catlett and Charles White, who would later teach and influence Kerry James Marshall’s art.

Two things should be clear from Wilson’s biography. He, along with White, Catlett, and their peers, were where the action was and, like them, his story centers on being a Black artist determined to be “a part of the narrative,” particularly in terms of what it was like to live in the US in the 20th century. In this regard, Wilson is both important as an individual artist and essential to understanding American history and art. In fact, an institution should organize an exhibition highlighting the artists, writers, and others who taught at the interracial Camp Wo-Chi-Ca — among them, Jacob Lawrence, Gwendolyn Knight, and the dancer Pearl Primus.

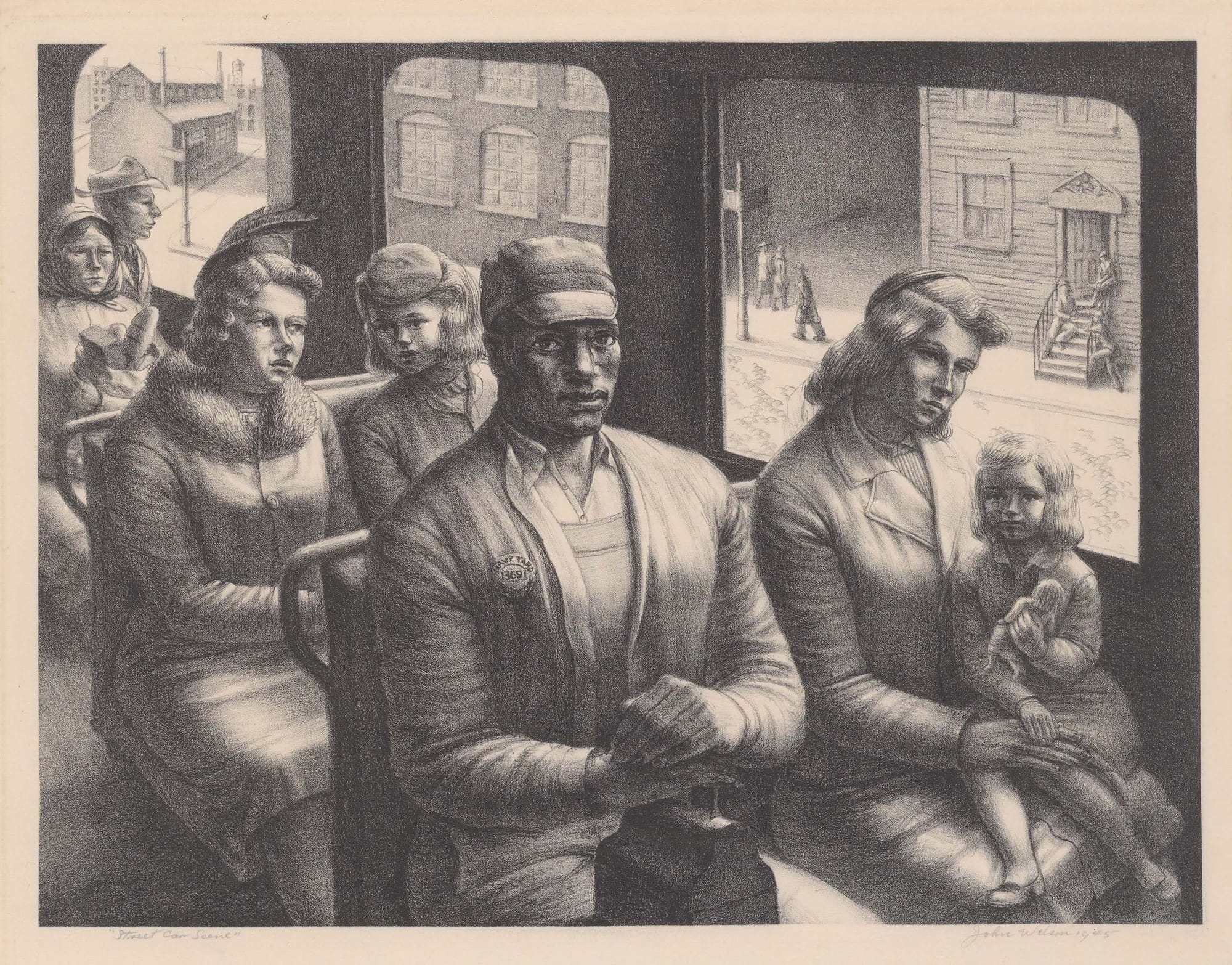

Wilson portrayed the gamut of the Black experience, making visible the sense of deep isolation, fear, and apprehension accompanying oppression and marginalization in the US, as well as pride, family, and community. His lithograph “Streetcar Scene” (1945) shows a Black Boston Navy Yard worker sitting in uniform on the streetcar, surrounded by mostly White women, all of whom ignore him. He looks at the viewer, his hands folded over his lunch box, dignified yet reticent, and highly conscious that he is the lone Black passenger. He seems to know in this situation that he must prove that he is nonthreatening — his uniform and button establish that he is a gainfully employed, productive member of society — and not interact with the other passengers.

Among the exhibition’s 100-plus works is a charcoal drawing of Martin Luther King Jr. The face is both idealized and weary, while the torso is schematic. The horizontal and vertical lines dividing the head and torso can be read as a sign of King’s martyrdom and as the crosshairs of the assassin’s rifle. Nearby is a commanding eight-foot bronze maquette of King’s head, which was modeled in 1982 and cast in 2021.

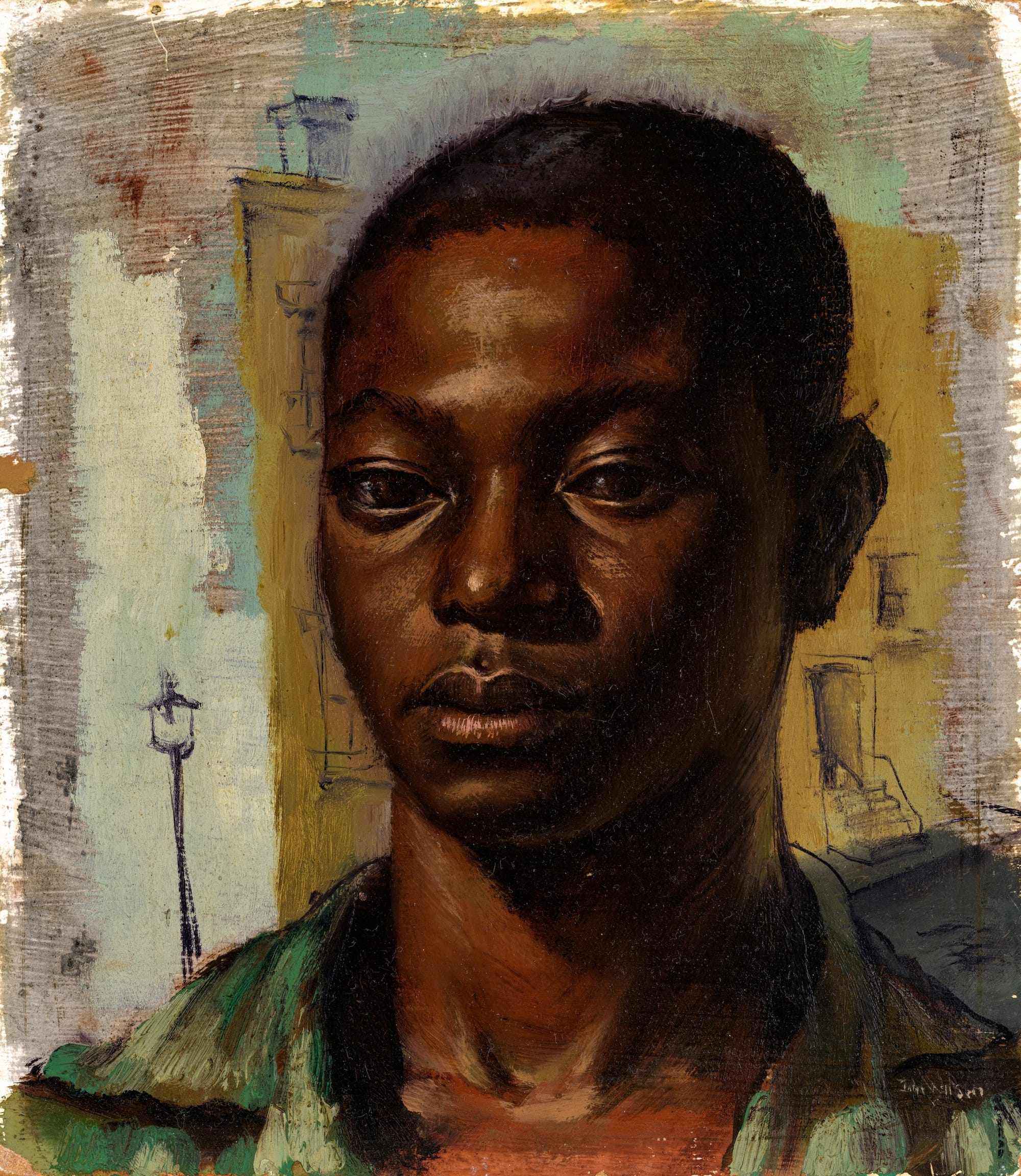

Also on view are pages from Wilson’s sketchbooks, including works from Paris and Mexico City that show him absorbing lessons from Léger and the Mexican muralists. I see these pieces as integral to his commitment to portraying the daily life of Black people in the US — their aspirations and fears. Anyone would have to have a heart of stone not to be moved by Wilson’s synthesis of empathy and artistic ambition. In the 2002 “Self-Portrait” and the lithograph “City Child (1965), Wilson, inspired by Ralph Ellison’s novel Invisible Man (1952), addresses the invisibility experienced in this country by people of color. In the prologue, Ellison writes: “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.” In a country where the president demonizes immigrants and people of color, Wilson’s work reminds us that beauty, art, and politics don’t have to be divided, and the right to be seen should never be decided by others.

Witnessing Humanity: The Art of John Wilson continues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1000 Fifth Avenue, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through February 8. The exhibition was curated by Jennifer Farrell, Leslie King Hammond, Patrick Murphy, and Edward Saywell.